This article, originally published in May 2014, is part of “Tales from the Expo,” an InPark Magazine online book written by James Ogul and edited by Judith Rubin.

Since retiring from the US State Dept in 2011 after a 30+ year career in world expos, Ogul has remained on the scene in an advisory and consulting role.

1980s Expo cluster prompts international call for BIE to reduce frequency…

[dropcap color=”#888″ type=”square”]T[/dropcap]he 1980s were jam-packed with world expos. There were world’s fairs in 1982, 1984, 1985, 1986, and 1988, and it took a toll on expo staffs for the countries that routinely exhibit at these events. In terms of international diplomacy and trade relations, one doesn’t lightly refuse an invitation to participate in a world’s fair, and the 1980s cluster of expos had many countries feeling the pressure politically and financially.

The US joined the resulting call for the BIE to reduce the frequency of expos which eventually resulted in the current spacing. The BIE took action, and now registered expos take place every five years with only one recognized expo being allowed in between. This much needed move will better insure that these events successfully continue into the future.

…and contributes to changes in how US pavilions are funded

The flurry of world expos in the 1980s certainly had a damping effect on US efforts to obtain funding from Congress and ultimately resulted in very restrictive budget language stating that federal money could not be spent on expos unless specifically authorized and appropriated by Congress. I remember the chairman of our appropriations subcommittee saying that he did not appreciate the White House making these commitments without first consulting Congress and then later requesting funds. In 1994, Congress hammered down on our Agency, restricting Federal funding. As a result, the US Government has had to rely on total private sector funding for US Pavilions in order to participate in a world’s fair. This was how the US was able to be present at Aichi 2005, Shanghai 2010, Yeosu 2012, and it will be the same for Milan Expo 2015.

Corporate support for US expo pavilions is an established practice. But total reliance on corporate funding brings additional risk and uncertainty to the situation. The budget for the USA Pavilion at Shanghai Expo 2010 was more than $60 million and in a recent video, the creative director for our pavilion planned for Milan Expo 2015 projected a $60 million budget.

It is an enormous challenge to try to design, plan and build a pavilion while simultaneously working to raise the money to pay for it. The US Government has tried to leave fundraising up to its private sector partner for these projects with varying results. For Aichi 2005 the private sector partner raised all of the money with a lot of help from Toyota. For Shanghai 2010, the private sector partner had little success and finally Secretary Clinton stepped in and fundraising took off. For Yeosu’s 2012 expo (South Korea), the private sector partner worked with the State Department, with Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Kurt Campbell doing the major fundraising for State. For Milan 2015, the State Department had indicated early on that it would not do any fund-raising this time, but considering recent past history and the kinds of challenges mentioned above, it seems possible that position could change.

TSUKUBA ’85

In keeping with the Technology theme of the 1985 world expo in Tsukuba, Japan, the US chose to design its Pavilion exhibits to illustrate Artificial Intelligence. The official selection of AI came from a panel assembled by the Woodrow Wilson Institute.

Tsukuba Expo ’85 ran March 17-September 16. The previous year, 1984, saw the Louisiana World Exposition in New Orleans, which would be the last world’s fair hosted in the US to date. Tsukuba was a much larger event than New Orleans. It was ranked a huge success with 20,334,727 visitors attending and 111 countries participating, plus an impressive array of 18 corporate pavilions featuring state of the art technology including robots and giant screen presentations. It was to be the last BIE-approved expo in Japan until Aichi 2005 – although the 1990s saw a flurry of non-BIE expos in Japanese cities until that country’s economic bubble burst.

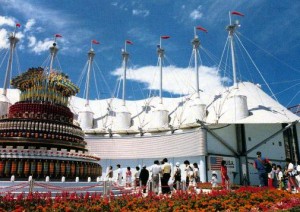

The 32,293 square foot US Pavilion at Tsukuba ’85 was in a generic building provided by the organizers, situated on a 53,821 square foot plot at the northwestern corner of the Expo grounds. It consisted of two courtyards, two plazas and three separate buildings: Theme Pavilion, Theater and Corporate Pavilion. The larger and taller theme pavilion to the right and the smaller Corporate Pavilion to the left were both housed under cable tensioned polymer fabric roofs. Between them was a Trapezoid Theater where “To Think,” a 15-minute film by Joseph Aloysius Becker, was shown. The corporate building which also included a restaurant and a gift shop housed exhibits by Texas Instruments, DuPont, Polaroid and TRW. The idea of separating out the corporate section was new to our pavilions and worked well. The corporate sponsors paid $259,063 in rent for the space.

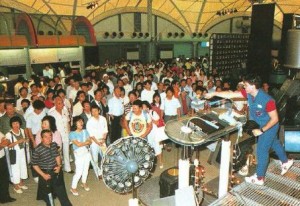

Artificial intelligence was a pretty advanced topic for 1985 and the goal was to impress the audience with the advanced state of research and development by the US in the field. In addition to the stand-up “To Think” theater, we had a Children’s Learning Lab, an Artificial Intelligence stage performance, the first transistor, a Kurzweil music synthesizer, and “Aaron,” a machine that drew original sketches. VIP visitors included Japanese Emperor Hirohito and Prime Minister Nakasone. The exhibits were designed by Herb Rosenthal in Los Angeles and were fabricated and installed by Nomura Displays in Japan. Boston Light and Sound provided the theater equipment and operation.

The pavilion’s restaurant was primarily a steak house but we added to that a take-out window that sold beignets using the same preparation as the Café Du Monde in New Orleans. The take-out window was so popular that the line of people waiting for a beignet was often as long as the line of people waiting to get into the pavilion.

Guides with walkie-talkies regulated traffic flow through the exhibits. They were fluent in Japanese and served for the entire 6 months of operation. Cars to be used by pavilion staff were donated by Mazda, Honda, Ford and GM. The largest car was a Lincoln, which provided for exciting trips through the narrow streets of Tsukuba. Corporate donations totaled $5,848,193 and were mostly in-kind. The exhibits were designed in Los Angeles and fabricated in Japan, and my job as Exhibits Director was to deal with the Japanese contractors, with the assistance of two engineers from our Army’s Camp Zama. The Pavilion team worked out of the US Embassy offices in Tokyo until the pavilion was ready for move-in. We commuted back and forth by train. [Read more about “student ambassadors” at US expo pavilions]

The US Commissioner General was Ambassador James J. Needham who also served as Chairman of the Steering Committee, the governing body of all international participants at the expo. There were two Deputy Commissioners General: Al Beach, a seasoned Expo veteran; and Hank Gosho, who incidentally had broadcast the first World Series Game back to Japan. The Federal budget for the project was $9,535,962. Attendance totaled five million visitors. The restaurant grossed $2,910,522 and the gift shop grossed 1,168, 000. As I have written about in a previous article, corporate support for US expo pavilions is a longstanding practice. But Tsukuba was significant in that a full 44% of the total project cost for the US pavilion was received from the private sector and the project ran a budget surplus. The success of the restaurant was notable, proving you can’t go wrong with steaks and donuts! It will be interesting to see how the US Pavilion restaurant at Milan Expo 2015 stacks up. [Read more about the role of the Commissioner General]

The Tsukuba experience overall was a rewarding experience for me. I enjoyed learning about Japan and the Japanese and was impressed by the Japanese work culture. Meetings with contractors would last well into the evenings, but after lengthy discussion and negotiation the work product was always excellent.

For my family, who accompanied me on all of my expo adventures it was an outstanding opportunity. My then five-year-old son attended a Japanese kindergarten and became fluent in Japanese. We are still in contact with his teacher some 30 years later. Our younger son had his first birthday there and my wife had many young mothers as friends in our apartment building. The Japanese diet and walking left us in the best physical shape ever.

VANCOUVER ’86

I got a call while on R&R in Hawaii on the way home from Tsukuba Expo 85 asking me to be US Pavilion Director for Vancouver Expo 86. I accepted and the family rerouted to Vancouver. Our two sons who had spent a year living in Japan now had to adjust to living in Vancouver. Arriving there, the expo was going up and had a similar look to Tsukuba coming down. It was a kind of déjà vu experience and a reminder of how close together expos had been occurring.

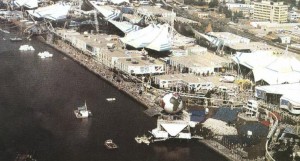

My first big cultural challenge was adjusting from my right hand drive Mazda in Japan to a white full sized Chevy Caprice (affectionately called Moby Dick) on the right side of the road. Expo 86 took place between May 2 and October 13, 1986, and as it turned out this would be the last Expo in North America, although Calgary made a failed bid for 2005, and Edmonton for 2017. The fair’s official title was the 1986 World Exposition on Transportation and Communications (it was nicknamed “Transpo”) and it boasted 51 national pavilions, including the United States, along with seven Canadian provinces, two Canadian territories, three US states and seven major corporations. An estimated 6.8 million

persons made a total of 22 million visits to the fair. This was far greater than projections. It is interesting to note that most attendance figures are recorded as turnstile clicks so the 22 million figure would be what would go down officially for Vancouver attendance, but at Vancouver they attempted to gauge visits vs visitors and hence the 6.8 million figure.

The United States section, including the US National Pavilion and the pavilions of Washington, Oregon and California, represented the largest non-Canadian presence at EXPO 86. The US Pavilion theme was the US Space Program. The Challenger space shuttle disaster had occurred three months before the opening of the Pavilion and President Reagan in his opening letter at the pavilion’s entrance stated, “The people of the United States dedicate their Expo ’86 Pavilion to the memory of the seven CHALLENGER astronauts and to the other brave Americans who have given their lives in the saga of space exploration. Their courage. their skill, and their willingness to assume great risk have taught the rest of us an invaluable lesson.”

Throughout the exposition, the US Pavilion operated at more than 98 percent of its capacity of 14,000 visitors a day. Two and a half million visits – over a third of the total of visits to Expo – were recorded at the US pavilion, including 15,000 dignitaries and special visitors. In addition, visits to the pavilions of California, Oregon and Washington totaled 7.5 million people. The Congressional appropriations for the U.S. Pavilion amounted to $6,850,000 spread over three years.

US participation at Vancouver was headed by Commissioner General and Ambassador Fred L. Hartley, the President and Board Chairman of Union Oil (later Unocal) Corporation. The Pavilion measured 25,000 square feet and had two floors. Visitors entered on the upper floor by climbing a ramp. Crowd flow was pulsed, with 200 people at a time pulsed through, based on crowd conditions within the pavilion. This was continuously monitored by guides using hand radios. A tour of the pavilion took approximately 30 minutes. Guides located at some 13 points throughout the pavilion gave presentations enhancing the visitors’ journey through some 40 years of space exploration. Written scripts were provided for each position, but the guides were given the flexibility to let their presentations evolve so that they could respond to the needs of their ever-changing audiences. The result was that all visitors received the same basic information, but the guides’ presentations were never quite the same from one to the next.

There was often a 30- to 60-minute wait to get into the pavilion. (By comparison the wait at the U.S. Pavilion in Shanghai Expo 2010 stretched as long as four hours.) Visitors entered the pavilion on the mezzanine level from an external skywalk, where the theme was introduced. Immediately inside the pavilion was the History Catwalk, where the visitors were greeted by a life-sized model of a Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), suggesting an astronaut working in space.

A History Catwalk showed the evolution of the American space program through scale models of the various spacecraft developed for it. Included were the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo spacecraft as well as the Pioneer, Voyager and Viking, the robot explorers of distant planets.

The Shuttle Marshalling Area outside the theater prepared visitors for a Shuttle launch. Visitors moved into a theater on the ground level of the pavilion for a six-minute flight aboard the Shuttle to a future when the planned Space Station would be operational. The voice of a NASA official at Mission Control provided a countdown. As the countdown continued, the sound of the booster rockets increased in volume until the entire theater reverberated with their roar as the Shuttle was launched. The film provided a glimpse of life aboard a spacecraft and simulated the Shuttle’s docking with the Space Station.

VIDEO of Tsukuba Expo 85 (clip #3 shows the US Pavilion)

At the end of the film the doors below the screen opened and visitors moved onto a space platform where they could view a scale model of the Space Station, complete with a docked Shuttle and astronauts working on the Station’s exterior. Visitors then passed through a pair of identical modules, life-scale mock-ups of living and working quarters aboard the station including experiments and living quarters sections.

Visitors to the US pavilion at Vancouver ’86 included such dignitaries as the Vice-President of the United States, the Prime Ministers of Great Britain and Canada, the Crown Princes and Princesses of Great Britain and Norway, the President of Italy and the board chairmen of General Motors and Chrysler. The pavilion received a favorable rating from 76 percent of the visitors, with 52 percent rating it good and another 24 percent saying it was excellent. At the time, this overall favorable rating ranked as the highest received by any American pavilion at a world’s fair since the USIA was formed in 1953.

The exhibit designer for the US Pavilion at Vancouver was Tosh Sakow who interestingly had also designed the Renault LeCar. The exhibits were fabricated and installed by Rathe Productions. Boston Light and Sound did the theater installation and the special lighting effects were by Donald Scarrow.

There were some fantastic exhibits at Vancouver including the renowned “Spirit Lodge” in the GM Pavilion designed by Bob Rogers & Co (now BRC Imagination Arts). His group also produced the excellent film “Rainbow War” (which received an Academy Award nomination). Also spectacular was the “Highway 86” outdoor themed area with a life size, climbable grey ribbon highway on which were an assortment of grey painted vehicles.

BRISBANE ’88

While I did not work on the US Pavilion at World Expo 88 in Brisbane, Australia, I did have the pleasure of visiting it while working on another project at Darling Harbor in Sydney. Opened by Queen Elizabeth, World Expo 88 was held April 30-October 30 in the year of Australia’s Bicentenary Celebration. Over 18 million people attended the fair, which had the theme, “Leisure in the Age of Technology.” The 98-acre site, located on the bank of the Brisbane River hosted 44 international participants and 23 corporate participants. The Commissioner General for the US Pavilion was entertainer Art Linkletter.

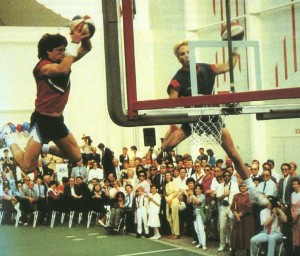

The US Pavilion theme was “Sport and its Science.” Attendance at the pavilion was approximately 5 million. In addition to the indoor exhibits, over a thousand American youths performed on a Sports Court in front of the Pavilion. Funding came from a combination of federal and private sector sources. After President Reagan had assured Australian Prime Minster Hawke that the US would participate, the US Information Agency requested and was granted by Congress approval to reprogram $2.6 million to get the project started. It then requested an appropriation of $8.2 million to be allocated over the next three years. That amount was reduced by $1,180,000 as a result of Gramm-Rudman restrictions, but additional money was raised through cash contributions and space rental fees charged to the three Pacific Rim States, Alaska, California, and Hawaii, bringing the total project budget to $9,742,067.

The exhibits in the 40,903 square foot pavilion featured a “People Wall,” a photo-montage depicting Americans participating in sports, a stylized “American Street” with scenes of children at play, an “Arena,” a vast hall ringed with areas devoted to specific sports, “Spirit,” an eight and half minute video projected in a large screen theater, a “Pros” area contained a professional sports halt of fame, and the “Strike Zone” where visitors could compare their throwing speed with professional baseball pitchers. A “Sports Technology” area educated the visitor on the development and refinement of sports equipment. The exhibits were designed and produced by Rathe Productions.

Alaska, California and Hawaii, each had their own exhibit areas within the US pavilion. Alaska staffed with groups of Alaskan citizens to act as guides. Each group stayed a month. A dog sled from the 1,600 km Iditarod race, an antique hand-made kayak and a giant stuffed Kodiak bear were among the exhibit’s highlights.

California presented a six-and-a-half-minute, giant screen video shot from a Landsat satellite, which had visitors swooping down from space then gliding across the beaches and mountains of California before zooming down to ground level at various destinations. Hawaii had a huge lighted resin sculpture of the legendary Duke Kahanamoku – the man credited with teaching Australians to surf. His original surfboard was displayed along with a number of contemporary boards that illustrated the contribution technology has made to surfing.

The pavilion’s two story “Americana” Restaurant was divided into six separate areas representing regional foods. The pavilion’s five million visits represented more than one-quarter of the total Expo attendance. A survey of Australian visitors to the US Pavilion indicated visitors rated the US Pavilion a solid “good.” An overall Expo-wide survey ranked the US Pavilion among the top ten in popularity.