Germicidal lighting fights pandemics and pathogens

by David Paul Green

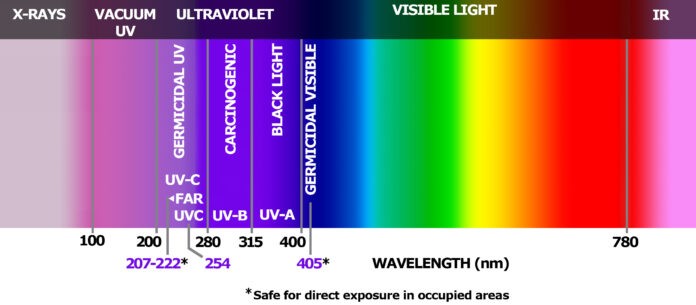

ABOVE: The light spectrum. Image created by Visual Terrain COO David Paul Green.

As the SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) pandemic appears to be winding down, the industry is working to transition back to something like normal operations. Certainly, owners and operators of themed entertainment venues welcome the return of guests.

However, there is uncertainty: Will Covid-19 ever fully vanish? Will it become seasonal, like the flu? Will we require annual vaccinations to fight new variants? And what if the next vaccine for the next pathogen can’t be developed quickly?

As scientists seek answers, one option being studied to manage future pandemics is germicidal ultraviolet lighting, aka germicidal UV or GUV lighting.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Lisa Passamonte Green, Founder and CEO of lighting design firm Visual Terrain, Inc., had a thought about an existing technology that could be applied: “We had already seen GUV lighting used in various healthcare environments. I wondered why it wasn’t used in theme parks, museums, casinos, offices, banks, live events, and retail? As our entire industry shut down, I knew we needed a way to reopen sooner, and germicidal lighting seemed a viable solution.” Green assembled an advisory panel of trusted colleagues, each member representing a different area of expertise required to implement germicidal lighting systems.

Lisa Passamonte Green, Founder and CEO of lighting design firm Visual Terrain, Inc.

Brian Buholtz, President of Buholtz Professional Engineering, a mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) engineering firm (air flow and HVAC)

Steve Birket, Vice President of Birket Engineering (life-safety systems)

Christine Marez, Vice President of Cumming (WELL buildings, energy and sustainability)

Mark Fergus, Regional Vice President of Cumming (cost and project management services)

“Outbreak prevention and recovery requires at least three components,” says Christine Marez, vice president of Cumming. “First: Bio-risk prevention through cleaning and safety protocols, and building-safety technology upgrades, like germicidal lighting, for improved air quality. Second: Sustainability planning. Improvements to increase ventilation may cause an increase in energy usage. We have to find alternative solutions to reduce energy usage, and still meet our carbon emission goals. Third: Communicating and messaging safety measures and technical improvements made in the entertainment environment to enhance the guest experience and build their trust.”

Brian Buholtz, president of Buholtz Professional Engineering, addresses the increased energy consumption that may result from trying to increase ventilation. “The CDC’s previous recommendations of six to 12 air changes per hour were not feasible in many applications. Here is an example: If you have a 1,000 sq. ft. office with 10-foot ceilings here in Florida, it normally requires about three tons of air conditioner. At six air changes per hour, that increases to nine tons!

“Current recommendations from CDC are more about increasing the ventilation, with more outside air,” he says, “but within the limitations of the existing equipment: Opening windows, maybe adding fans on a nice day, adding HEPA filters. The CDC also includes discussions about directional air flow – forcing air in a direction that would reduce direct person-to-person transmissions – and they also talk about GUV lighting. All other technologies, they consider to be emerging.”

What is germicidal lighting?

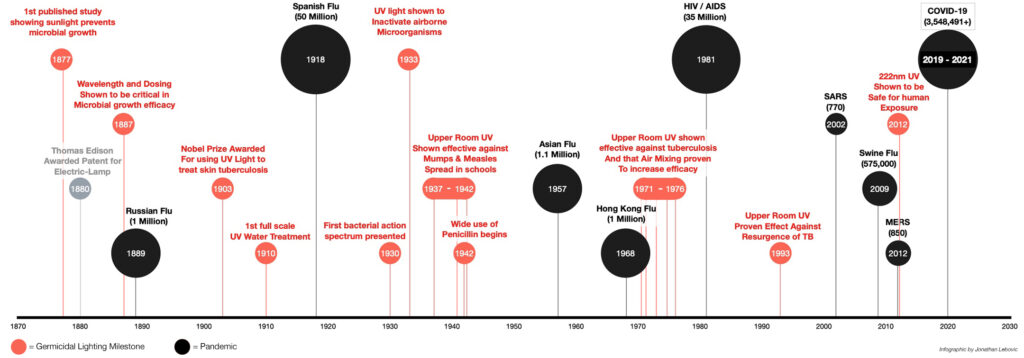

Although germicidal lighting may be new to many people, it was first discovered in 1877. By 1903, UV light was in use to treat tuberculosis, and in 1910, it was first installed in a water treatment plant. A 1937 study in Pennsylvania showed it was effective at preventing the spread of some childhood diseases in public schools: first, mumps and later measles. For a time, it seemed germicidal UV might become widespread; then in the 1940s and 1950s, antibiotics and vaccines came into use.

The global availability of treatments – for measles, tuberculosis, polio, and others – effectively displaced germicidal UV as a means of disinfection, although it continued to be used in infectious disease clinics, hospitals, and other high-risk medical environments.

——

There are three primary methodologies of UV disinfection:

- Surface disinfection, where UV light is directed to visible surfaces (walls, floors, tabletops, counters, etc.) to kill pathogens on those surfaces.

- Ventilation disinfection, where UV systems are installed into HVAC units or ducts, to disinfect air as it passes through the system, and/or disinfect the coils.

- Upper-air disinfection, where UV sources are directed above occupants’ heads, to clean the air near the ceiling of a room, and inactivate pathogens as they are circulating.

Upper-air disinfection is most promising against airborne pathogens, such as SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), but it is not as effective against pathogens that are spread primarily through surface contamination. Pathogens that easily spread from room to room may be better handled through ventilation disinfection. Hospitals may use all three methods: surface disinfection in the operating room, upper air disinfection in a waiting room or ER, and ventilation disinfection throughout.

There are three wavelength spectra of UV light: UV-A, UV- B, and UV-C, defined in nanometers (nm) ranging from approximately 200nm (Far UV-C) to 315nm (UV-A).

UV-C is the wavelength that offers the most promise for germicidal lighting, as it can be both safe and effective when properly implemented. (UV-A is ineffective, while UV-B is carcinogenic.) Although some wavelengths of UV-C may cause temporary skin and eye irritation, it does not cause permanent damage, and is not considered carcinogenic. “Far-UV-C” light, between 207nm and 222nm, appears to be entirely safe for eyes and skin.

254nm UV-C light has been safely used for over 90 years, and continues to be studied for its potential to deactivate pathogens. Some manufacturers of lighting products are now turning their attention to 222nm Far UV-C light, as a possible tool to disinfect surfaces, and even the air in a room. Manufacturers of existing UV-C fixtures that had previously only been sold to medical facilities, are pitching their products to other venues.

“UV-C light disrupts DNA,” says Steve Birket, vice president of Birket Engineering. “That’s why it renders viruses to be unable to reproduce. In people and animals, it can damage the skin and the eyes. The analogy here is that of a fire: When managed, it gives you warmth and light, and it’s desirable. Like a fire, exposure to UV-C lighting is about intensity, proximity and time. On the skin, overexposure to UV-C light presents like a sunburn. With eyes, aversion to bright light is the natural response, but that doesn’t work with invisible UV-C, so people can’t feel the negative impact right away. Overexposure to UV-C lighting to the eyes presents as pain, redness, light sensitivity. Safety considerations with UV-C lighting are about containment of the light, and when it’s not about containment, it’s about occupancy. Containment is a situation where the virus is exposed, but the people are not: The light is not available to your skin or eyes, such as in an in-duct HVAC system, or an upper-air system. Where the light is not contained, a combination of occupancy sensing, interlocks, site procedures, and user behaviors provide safety.”

“Over the past year, several manufacturers have developed some great products,” says Green. “But there are also products to be wary of. I’m worried that owners and operators are going to invest in harmful and ineffective products, and it will slow the adoption of a technology that could be extremely helpful if it’s done correctly.”

What are the GUV adoption challenges?

While companies are developing long-life lamp solutions, the current technological standard – 254nm UV-C tubes – must be replaced as often as quarterly. While the tubes are not expensive, ensuring they are “fresh” can be a recurring labor expense that venue operators may find burdensome.

Some believe the risk of possible eye and skin damage is simply too much of a legal liability. However, when UV-C systems are properly designed, applied and implemented, these risks are easily mitigated and managed. Green says, “The financial risk of doing nothing to prepare for the next pandemic is far greater than applying this technology now.”

Another downside is that municipalities are not yet ready to treat a venue with germicidal technology installed any differently than one without it: If there is another surge, everything still gets shut down. This may change, but as of now, venue owners must lobby government to acknowledge the effectiveness of germicidal technology and allow businesses that implement it to remain open.

Acquisition cost is another challenge to implementation. Costs range from a few hundred dollars for a simple upper-air fixture, to hundreds of thousands of dollars for high-tech, disinfecting robots. To determine the cost for a facility without an in-depth feasibility study is difficult, as there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Not being able to assign a cost-per-square-foot or dollars-per-room number to an installation prior to a study makes owners rightfully wary.

On the positive side, manufacturers are working to develop systems with built-in safety and monitoring features. Many respected and trustworthy companies, such as Christie, Acuity, Cooper Lighting, and Philips, are developing germicidal lighting products for environments beyond healthcare. Companies such as Synexis are taking the technology in new directions, using UV light to generate dry hydrogen peroxide that can inactivate pathogens in an occupied room, with no risk of UV exposure at all.

What’s Next?

Venue owners are advised to do the following things when considering germicidal technology:

- Ask to see third-party product or use studies that were not paid for by the manufacturer.

- Contact government leaders and ask them to make installing germicidal lighting a factor in shutdown guidelines.

- Research! The technology is advancing rapidly. Some is ill-conceived or inefficient. There is no silver bullet. Get comparisons: Don’t just buy from the first salesperson who comes along. Determine the right application of this technology for your specific environmental health and safety needs. When chosen properly, guests and employees will be confident that visiting your venue is safe.

Birket notes, “The themed entertainment industry is good at taking a constraint and turning it into a special effect. There are always possibilities. There’s a lot of ingenuity out there.”

Mark Fergus, regional vice president at Cumming, adds, “It’s about early adoption. Theme parks are known as somewhere to go and have fun, but also to have fun safely. So we’re reinventing ourselves and caring for our staff and our consumers.”

Marez adds, “It’s time to be proactive and not reactive, and really consider getting a wellness or healthy building certification for your theme park or venue, so that when your guests arrive, they feel comfortable in knowing that you took the care and went above and beyond to make sure they were safe.”

Finally, Green concludes, “Our industry is filled with compelling places and experiences where people gather, and germicidal lighting is a technology that will allow that to continue for years to come. You just have to look at how you can implement it, how it can be done safely, how it can make a difference, and what happens when the next pandemic rolls around.” • • •