2021 American Alliance of Museums Virtual Conference asks the tough questions

By Clara Rice, JRA

InPark Magazine is grateful to Clara Rice for sharing her editorial insight into the AAM Virtual Conference. A long-time contributor to InPark, Clara is the Director of Communications for JRA, a master planning, design, and implementation studio that creates immersive experiences for theme parks, museums, and branded attractions worldwide. She currently serves on the International Board of Directors for the Themed Entertainment Association (TEA) as Global Sponsorship Chair, and speaks at industry conferences around the world.

For the second year in a row, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced museum professionals to gather virtually for the American Alliance of Museums’ Annual Meeting and MuseumExpo, versus in-person at its planned Chicago location. But unlike last year, cultural institutions have now had 15 months to reflect not only on the pandemic itself, but also on the cries for justice following the murder of George Floyd, Breona Taylor and too many others, the tumult of academia as students and teachers navigated virtual learning, and the gross inequities that COVID brought out of the shadows of theory and into the glare of reality.

While there were moments of joy and laughter throughout the conference, such as a cameo appearance by CBS Sunday Morning correspondent Mo Rocca, an interactive performance by legendary improvisational troupe, The Second City, and a behind-the-scenes virtual tour of Chicago’s most popular venues, the majority of the four-day event featured difficult discussions on how museums must acknowledge their past, assess their present, and anticipate their future in order to achieve resilience in a post-COVID world.

Resilient, Together

In keeping with the conference’s theme of “Resilient, Together,” AAM President and CEO, Laura Lott, warned of the “myriad challenges” ahead but also reminded attendees of how far the industry has come since the pandemic began. As a result of last year’s Annual Meeting, museums began asking themselves “what aspects of traditional practice have not served us well – as professionals and institutions? And how can we rebuild more sustainably, more equitably? What is the role of museums in bridging divides, bringing communities together, and fostering empathy, understanding, and belonging?”

By engaging in this internal reflective work, museums have become better at not only identifying opportunities for growth, but also identifying the characteristics that make them essential community assets. In Spring 2020, one-third of all museums reported that they were at risk of permanent closure. It was clear that, to survive, cultural institutions would need government support. With the help of AAM, museum advocates sent over 60,000 messages to the U.S. Congress, resulting in an amount of government funding unprecedented in the 115-year history of the Alliance. Now, less than 15% of museums claim to be at near-term risk. Lott described this achievement as “the collective power when we come together” but cautioned museums to not to rest on their laurels. Instead, cultural institutions must embrace a spirit of renewal in pursuit of a more equitable future.

“Our museums have the opportunity to be leaders in rebuilding, to be the promise for recovery and catalysts for reimagining our communities – stronger than they’ve ever been,” Lott explained. “There is no place for hesitation or fear in the next steps that we, as a field, must take in the coming months and years…We must boldly challenge the status quo, rethink outdated models, and lift up the many brave individuals in museums across the globe who are leading us into new frontiers.”

Acknowledging the Past

Before museums embark into new frontiers, many cultural institutions must first acknowledge some uncomfortable truths about their pasts.

In 2007, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) adopted the following definition of museums: “a museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study, and enjoyment.” Since the association’s 2019 Triennial in Kyoto, ICOM members have grappled with how this definition needs to change. Rick West, ICOM member and President and CEO of the Autry Museum of the American West, covered this conundrum in his session “The Great Debate: What is a Museum?” “The question,” he revealed, “is whether we are prepared in any way to move from that particular construct to a different construct of museums in the future.”

According to renowned lawyer, speaker, and activist, Bryan Stevenson, a new construct must be acknowledged and embraced, whether we as an industry are prepared for it or not. Acknowledgement of uncomfortable truths is the only way that museums can reckon with their pasts and learn the necessary lessons to rebuild. Confession, repentance, and truth-telling, asserts Stevenson, are the sole methods for achieving reconciliation and redemption. Museums cannot possibly know how to mitigate past damage if they have not determined the nature of that damage in the first place.

In her panel discussion, “Truth Before Reconciliation: Taking the Requisite Steps Toward Resilience,” Jaclyn Roessel, Cultural Justice and Equity Consultant for the US Department of Agriculture, explained that the most glaring truths for museums to acknowledge are their colonialist, Eurocentric roots. “So much of the harm that begins to be created comes from the stolen labor and the stolen land that has created the foundation of this country and of museums…a lot of the beginnings of that cracking consciousness and accountability can stem from naming where we are, how we come to existence, and then simultaneously what we are doing.”

Having acknowledged their foundational truths, museums can begin determining how these colonialist origins have shaped their institutions through the decades. Who have they historically prioritized – their visitors, their boards, or their objects? Whose stories have they told, or not told? How have they acquired their collections? Are their collections predominantly heteronormative? Ableist? White? Who have been their principal storytellers – their curators, their trustees, or their guests? Who have they received donations from? Have they been essential to their communities? If not, what factors have created barriers to becoming essential?

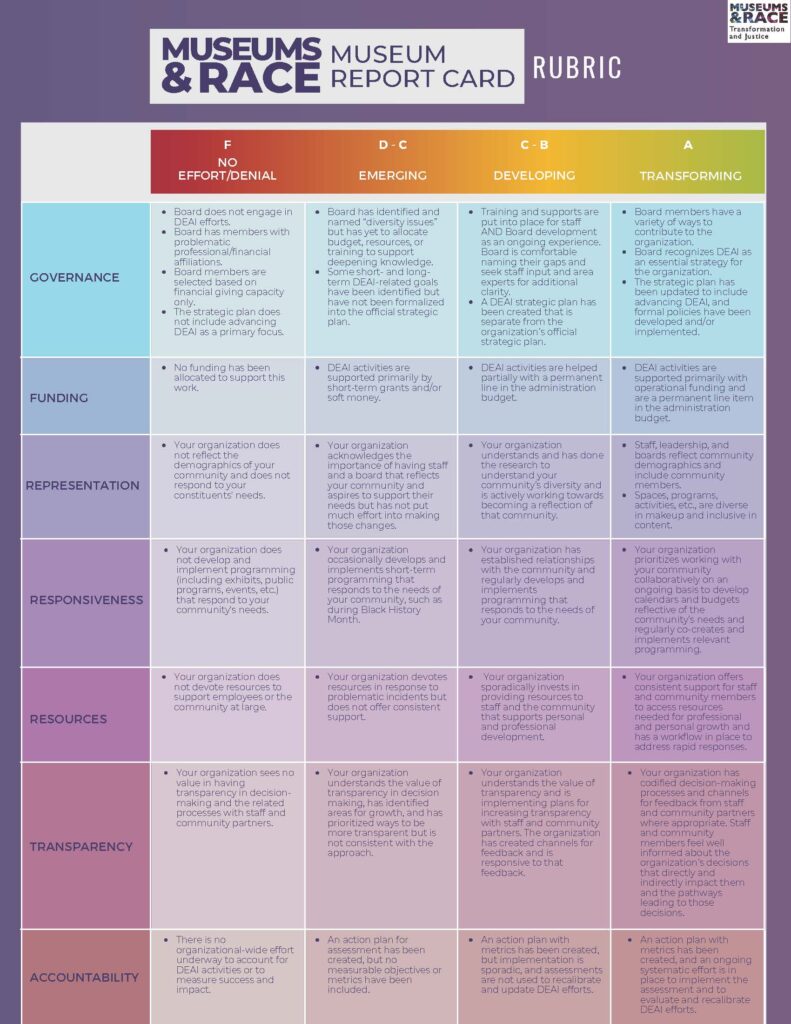

With these answers in hand, they can begin the process of Stevenson’s redemption, salvation, and restoration as they share their reconciliation plans with their communities and establish systems of accountability. As panelist, Janeen Bryant, Principal of Facilitate Movement/Museums & Race explained, this critical step is typically where cultural institutions encounter the most resistance. “My first call to action is to stop the fretting and pearl clutching and the knee knocking complicity that I see happening all over the country, where people are pretending that…there’s going to be some pushback before they have ever even tried… We will fail at this several times, but there is no winning to DEIA conversation and there is no winning for reconciliation, it’s an ongoing process…To be in relationship with our community members, we are going to have to push into these spaces that we haven’t.”

Assessing the Present

Once museums acknowledge the depth and breadth of reconciliatory work needed to deepen trust with internal and external stakeholders, how do they push into those uncharted spaces on a path toward resilience and healing?

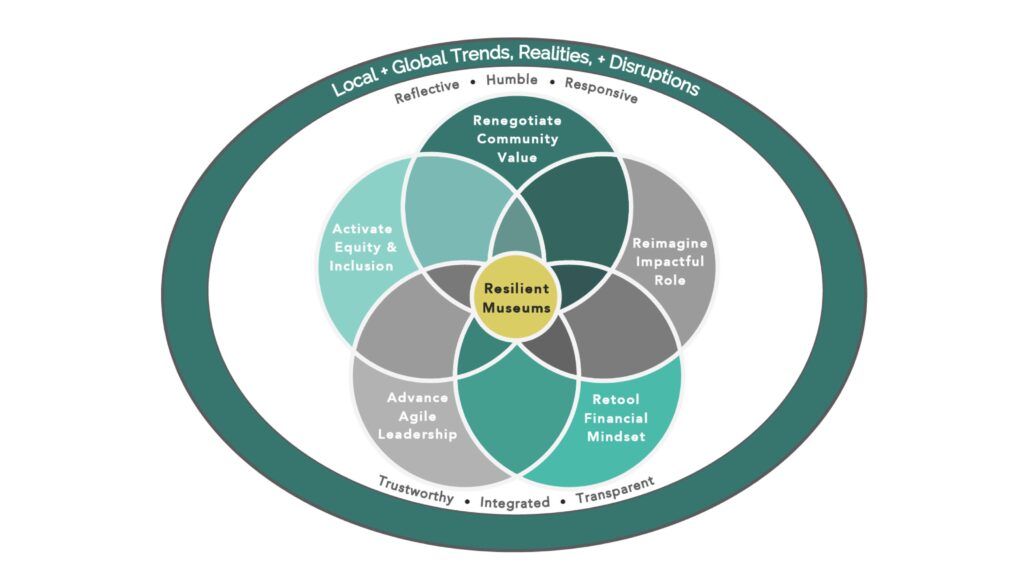

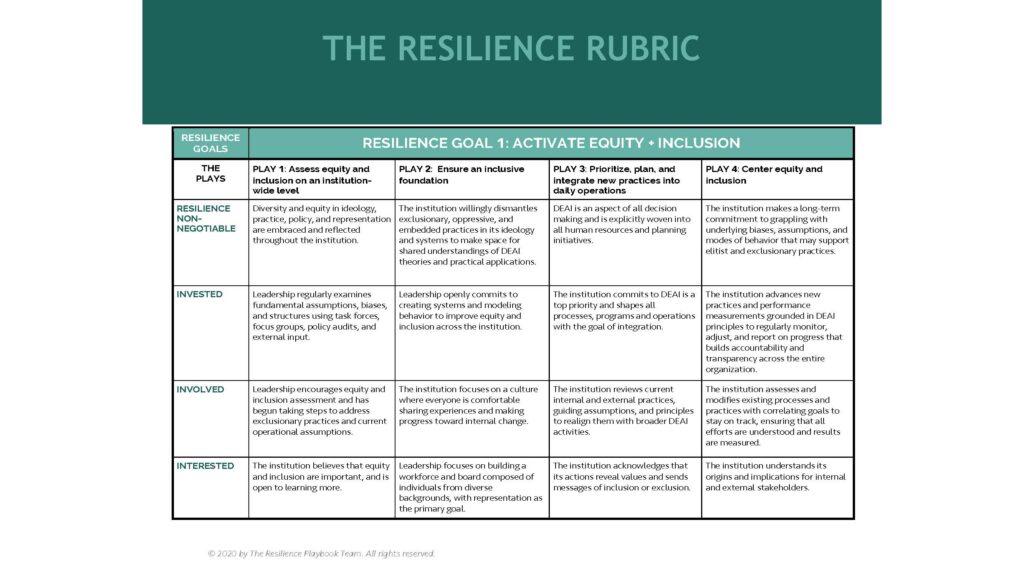

In their panel “Resilience for Museums: Strategies to Address Changing Realities,” Anne Ackerson, Melanie Adams, Gail Anderson, Dina Bailey and Ben Garcia revealed what they are calling the “Resilience Playbook” – a proactive organizational framework comprised of five goals that enable museums to respond to disruptions, identify and remedy exclusionary practices, navigate community relationships, and foster greater organizational alignment.

The first goal of the framework is to “activate equity and inclusion.” Organizations need to develop a “shared language” and “specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound actions,” that involve abandoning historically colonialist structures, fostering empathy, and adopting inclusive practices at an industry-wide level. Examples of methods for activating DEAI could include adopting a universal, anti-ableist design approach to museums’ buildings, exhibits, and member communications, offering such tools as audio description, captions, interpreters, and tactile experiences. It could mean eliminating donation minimums for prospective board members, since BIPOC have historically not had the same opportunity to accumulate wealth. Or it could mean engaging in the difficult work of formal anti-racism training.

“Let’s be honest,” said Anderson. “We’ve made terrible progress in the field, not only in attitude and the reflection of our staff and especially in our boards and then reflected diversity in our collections…For institutions to really think and understand equity and inclusion, they have to do some deep reflective work and anti-racism training. I think that equity and inclusion has tended to be a numbers game, and it’s not. It’s attitudinal, it’s holistic, it needs to be integrated into the entire operation and a core value.”

After activating equity and inclusion as a core value internally, museums can then “renegotiate community value” externally, redefining their organizations as “integral, relevant, and vital to public life.” How can museums leverage their programming, collections, outreach, and partnerships to become true players in their communities, the industry, and even the world? Throughout the pandemic, museums demonstrated their unique value propositions in a variety of ways – from serving as study spaces for remote learning, to transforming into temporary vaccination clinics, to distributing food to those in need. How can museums perpetuate this level of community engagement even when they are operating at full capacity in a “normal” year?

In conjunction with renegotiating community value, museums need to “reimagine their impactful role” and “reinvent the organization for the greatest relevance.” They need to reexamine their mission and vision statements to ensure that they are focused more on communities and less on collections. They need to cement their commitments to “agility and resilience” through “meaningful and inclusive practices” that champion positive change and are consistent regardless of the any external trends, disruptions, or sociopolitical forces.

Museums cannot fully commitment to operational, programmatical, and social change without also retooling their financial mindset, the fourth pillar in the resilience framework. According to the panelists, museums need to “take a hard look at financial realities and instill new habits,” developing clear strategies to address wage disparity, minimize vulnerability, mitigate risk, and align their investment and procurement policies with their values. What is the compensation gap between the Executive Director and the lowest paid employee? How financially literate are staff and board members? Is the museum just using the same vendors they have always used, and if so, are there avenues to expand that circle? Does the museum have an investment policy that is consistent with its DEAI initiatives? As panelist Ben Garcia explained, “where you put your money is a documentation of your values…your budget is a moral document.”

While the preceding four goals are important tools for resilience, none of them can be fully achieved without the fifth – advancing agile leadership. Without buy-in from the top, meaningful change becomes challenging if not impossible. Equally important, however, is for leadership, staff, board members and volunteers to work in tandem. Museums need to move “away from this idea of the heroic leader to have just a larger ‘Justice League of folks’ in the organization,” said Garcia, “so that …the goals of the organization don’t get derailed when the executive director leaves.” They need to transition from “hourglass shape” – comprised of trustees on one end, staff and volunteers on the other end, and the Executive Director in the middle – to a “cylinder so that there are many more points of connection between trustees and staff and stakeholders.” This cylinder creates a “holistic, integrated, and inclusive leadership model that can articulate the museum’s values, address its shortcomings, leverage its assets, maximize its potential and secure its future.”

Together, these five goals of the Resilience Playbook result in museums that are more agile, flexible, responsive, and inclusive. “When we talk about resilience, we’re aren’t really talking about being able to bounce back from a bad situation,” said Ackerson. “I think that that’s been reactionary. When we define resilience, we’re looking at this understanding that institutions are able to anticipate change and they’re able to do that precisely because they’re aware of what’s going on inside and outside their organizations. They are engaged in deep methodical internal work, and they are staying focused on how this all fits together.” By becoming more sustainable, collaborative, empathetic and essential, museums and their communities can work together toward a more resilient, compassionate, and progressive future.

Anticipating the Future

Few museum professionals have focused on the future more than Elizabeth Merritt. As AAM’s VP of Strategic Foresight and the Founding Director of the Center for the Future of Museums, Merritt has been tracking trends for over 22 years. Her annual publication, TrendsWatch, typically identifies the emerging tools, technologies, and societal shifts that will shape the future of museums over the next ten years. Past reports have covered such change agents as government funding, decolonization, agile design, and blockchain.

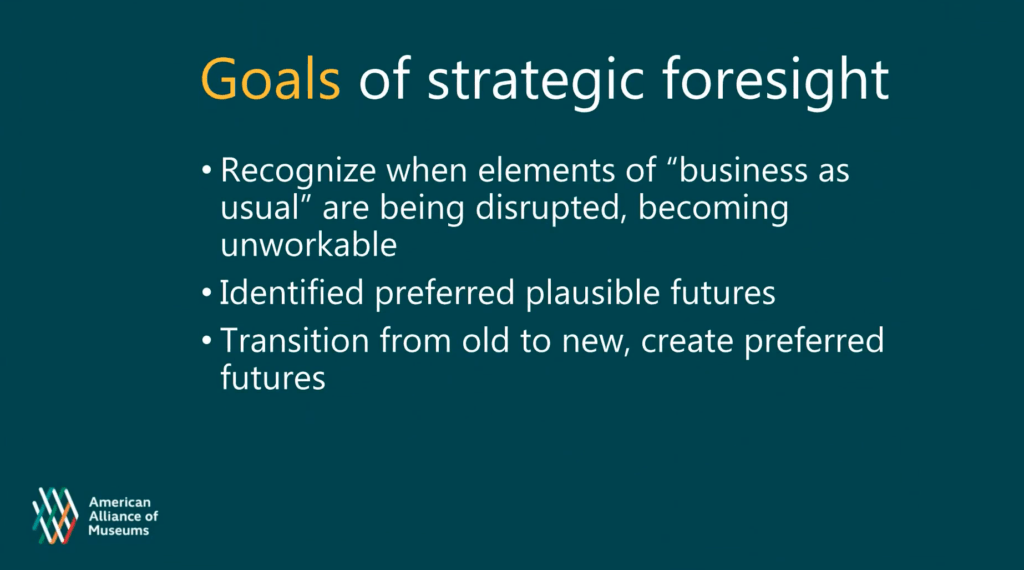

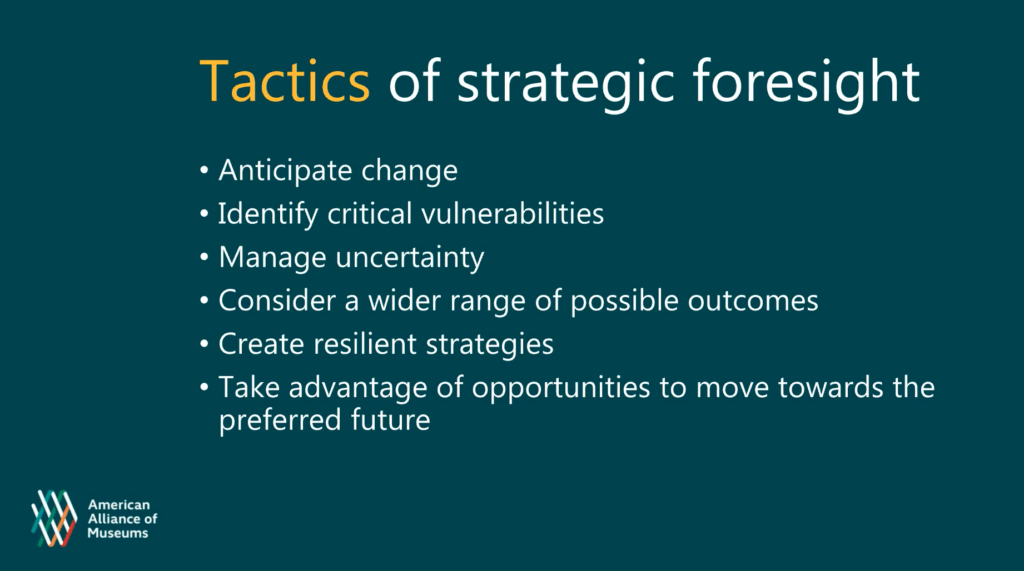

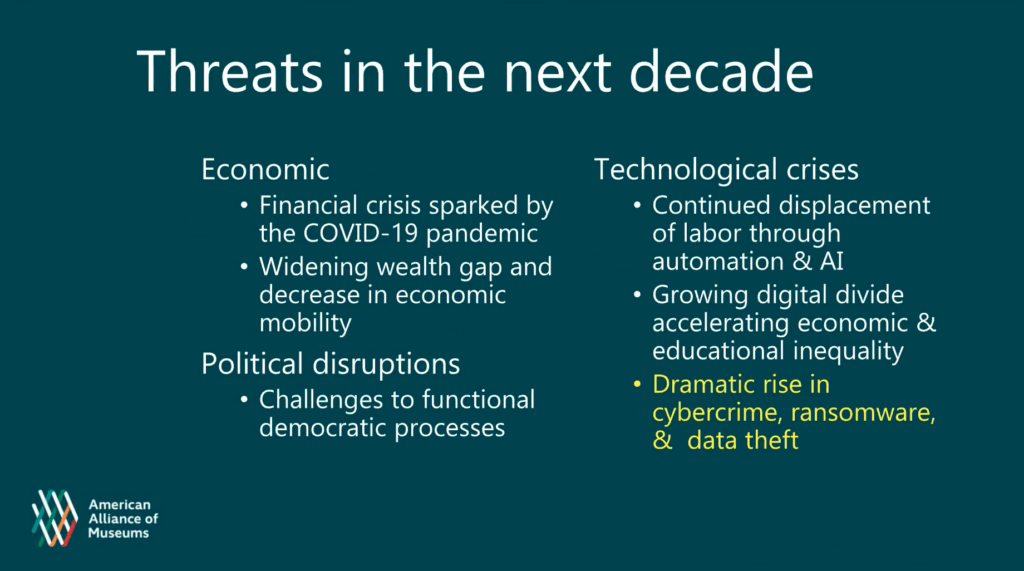

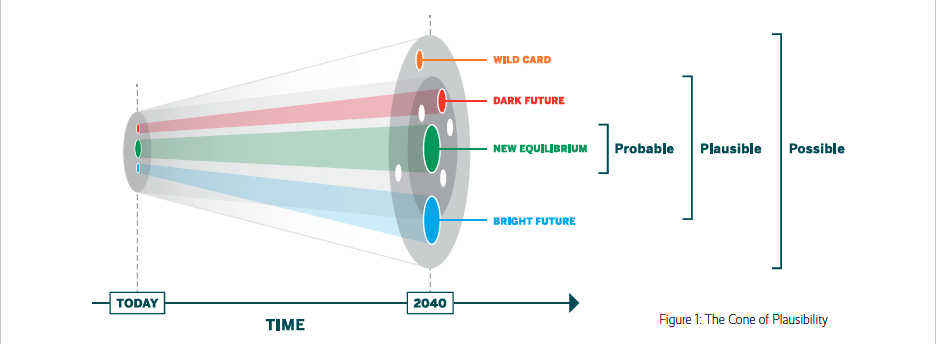

As Merritt concedes in her AAM Virtual session, “TrendsWatch: Navigating a Disruptive Future,” 2020 and 2021 have been anything but typical. The fear and uncertainty surrounding COVID-19 has shaken museums their core, and, as identified by so many other AAM sessions, challenged the industry’s established norms and behaviors. While the pandemic has forced many museums to operate in reactive mode in the face of ever-changing policies and procedures, it has also forced them to adopt a proactive planning approach in order to prepare for future disruptions. One such approach, “Strategic Foresight,” serves as the cornerstone to Merritt’s 2021 report and AAM virtual presentation, and she believes it is critical to museums’ long-term survival.

Merritt defines Strategic Foresight as “the practice of systematically observing current events and using the findings as a springboard for envisioning potential futures. It is a way to both expand the imagination and compress uncertainties into a manageable number of possibilities.” By exploring a range of potential positive and negative outcomes, determining historic practices and current systems that could propel a museum towards those outcomes, and identifying a preferred future outcome, Strategic Foresight is dependent upon and yet a continuation of acknowledging the past and assessing the present.

To demonstrate this approach, Merritt offers the four example future scenarios of Growth, Constraint, Collapse, and Transformation. Faced with a Growth scenario, “characterized by abundant and increasing resources,” museums may want to expand their programming, launch a capital campaign, or otherwise take advantage of their visitors’ and donors’ more ample discretionary income. Constraint, either internal or external, could force museums to do “more with less” and develop new innovative models in the face of scarcity. Collapse, felt by many museums over the last year, could involve a complete structural, organizational and financial overhaul. Transformation, defined as “an unexpected sideways leap that creates an unfamiliar world,” could revolutionize the way that museums do business, adopting ideas never before imagined. Merritt cautions that these scenarios or not predictions, but merely a “range of possibilities” that “avoid either overly optimistic or pessimistic thinking.”

To embrace Strategic Foresight, museums must determine what outmoded elements of the organization are susceptible to collapse in the face of disruption and then disavow those historically unsustainable practices, thereby acknowledging the past. They can then scan the current environment to ascertain any potential threats to their preferred envisioned future, thereby re-assessing the present. Only with their past inequities and inefficiencies addressed and their current environment explored can museums begin envisioning a preferred future for themselves and their communities. They can then determine the necessary steps to turn that vision into a reality.

The Work Continues

While the work of acknowledging the past, assessing the present, and acknowledging the future seems like it would have natural beginning and end points, as AAM President and CEO Laura Lott notes, “this work is ongoing and, in fact, it likely won’t ever be complete.” Only through a perpetual cycle of self-reflection will museums inch closer to a more equitable, sustainable, and just existence – not just for themselves, but for their communities and society at large. Luckily, because of their focus on creativity, conversation, and connection, museums are the most apt organizations to be performing this difficult work, which is why so much of the AAM Virtual Conference consisted of “tough love” messages toward its member institutions.

“We can lift of the voices that are too often left unheard,” explained Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole, President & National Chair of the National Council of Negro Women, Inc., in her introduction of Bryan Stevenson. “We can inspire a curiosity and creativity. We can combat hatred and disinformation, and we can foster empathy and understanding and love…I believe…that museums have the ability, and more importantly, the responsibility, to play a leading role in our country’s truth, reconciliation, and healing process.”

“When museums contribute significantly to myriad aspects of public life, when they help build racial equity on a local and national scale, when they’re part of the safety net caring for the most vulnerable, when they play an essential role in education, when they serve as a go-to trusted source of information, when they step up to care for their communities in a time of crisis, that to me is the new stable business model for the field as a whole,” said Merritt. “When people know that their lives, their communities, and the nation would be poorer and more broken without museums, individuals, businesses, donors and the government will make sure museums endure to serve future generations.”