By Dr. Kathryn Woodcock

As a deaf person, human factors engineer, educator and specialist in themed entertainment, Dr. Kathryn Woodcock, P.Eng., C.C.P.E., I.C.A.E, has key insights to share with the industry. She is a professor at Ryerson University, teaching about accident theory and analysis, safety evaluation techniques, and health and safety systems. At the graduate level, she teaches about themed entertainment technology and design in the Master of Digital Media program. This article is the second of her exclusive, three-part series for InPark, addressing issues of accessibility and inclusion in attraction design. (Click for part 1, “I am not an ‘ADA Guest.’”)

When do accessibility and inclusion come in during the process of designing a ride, attraction or other guest experience? As with any kind of performance shaped by design, the best time to consider inclusion is before the design is finalized. The second-best time is now.

It can be easier to understand where barriers occur if the experience is already operating, and guests are identifying their concerns. However, the need to make modifications after missing the early design window is a major factor in why accessibility is associated with cost.

How to consider access and inclusion early? Is it an audit of the finished design, and a punch list of modifications, add-ons, and operational procedures to comply with ADA? Do you do a runthrough of the guest journey for each of a list of personas to identify alternate facility and procedure needs as the design shapes up?

While there are many such schemes, I am always troubled by using a finite list of discrete items for an analysis of something as infinite and continuous as accessibility. Instead, I recommend beginning with the question, “What does this experience ask of the guest?”

This does not mean, “What body parts does a guest need?” or “What sensory abilities must they have?”

It means, “What do they need to understand?”; “What do they need to do?”; “What do they need to tolerate?”; and even, “What must they resist?” along the guest journey, to enter the space, sit, stand, or walk through the show or ride, enjoy the experience, maintain a safe posture through dynamic forces, and exit at the appropriate time, in the appropriate way.

Start systematically

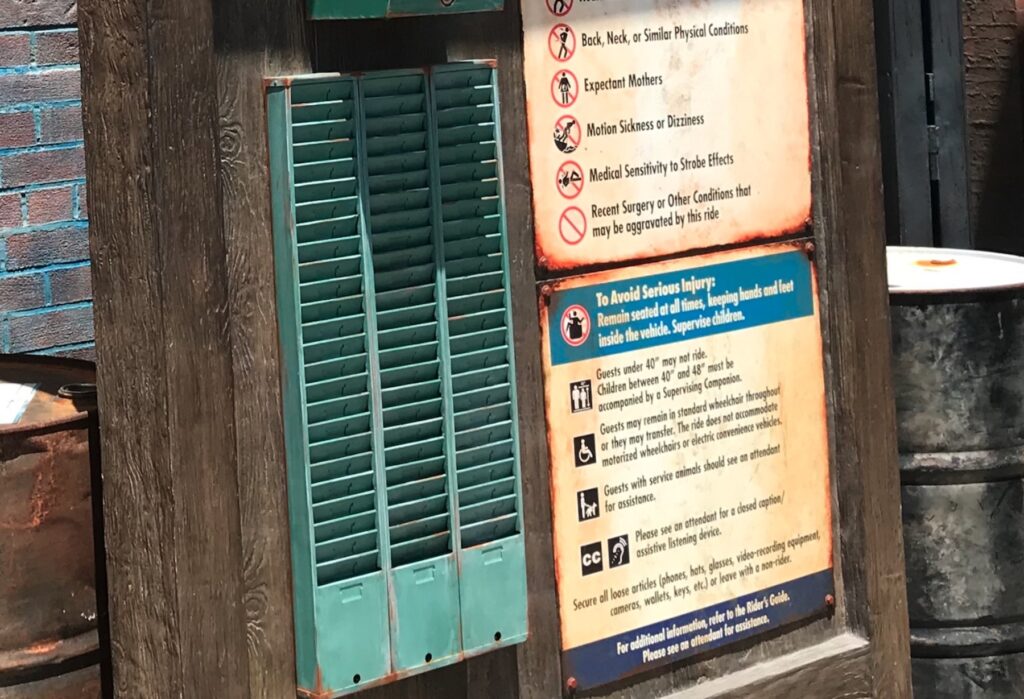

The most systematic way to approach this is to start with a breakdown of the experience, scene by scene, second by second, metre by metre. Just as we would identify peak ride forces that require restraint devices, padding, and positioning devices, or plot points that rely on prior knowledge of the IP and call for some backfill context for less familiar guests, we will look at the breakdown and identify spots that require a specific capacity from the guest, or impose physical or sensory challenges that a guest must tolerate, such as pressure on their body, acceleration, vibration, loud noises, phobia triggers, flashing lights, mist, and scent.

Multiple strategies are even more important when what the attraction asks is not just for enjoyment but for safety. If a guest needs to resist acceleration to maintain a posture during a dynamic ride experience to avoid serious injury, arm amputees and people with weak core muscle strength may be excluded. The need for functioning arms and hands to brace is not inevitable – it is created by the restraint and containment system selection. If a guest needs to be aware that a response is needed for their safety, and the cue to make that response is presented only in visual form, blind and partially sighted people may be excluded. The need for vision is not inevitable – it is created by the way information is presented.

While people can dynamically brace with their arms and hands, providing additional restraint devices can support those who cannot brace. While people can read or observe visual indications, audio information can inform those who cannot see.

Examine assumptions

The greatest challenge in reviewing the breakdown is to take certain capacities and characteristics for granted. The only ability we should take for granted is tolerating a stationary position of their own choice at room temperature. Even being able to hold a different specific position in a slow-moving vehicle, should be noted and considered. This does not mean an attraction should require no more than that. However, we need to acknowledge all other requirements and determine if we have created any access restrictions that could be avoided by revising the design.

Despite the best of intentions, even with unlimited creativity, there may be technical limits, resulting in an experience that asks more of guests than some can meet, but this should never be due to mere assumptions.

Inclusive or exclusive?

When we identify access modifications we need, inclusive design is typically seen as the ideal. Inclusive design means anyone can access without any specific measures being taken. Using open captions, instead of activating closed captions on demand, accommodates deaf and hard-of-hearing guests, and also guests who can read English but struggle with spoken English, while having little or no negative impact on other guests. In some cases, achieving inclusive design can be challenging with existing attractions, where architecture and media modifications are impossible or prohibitively complex or costly.

Alternate amenities may also be satisfactory: alternate facilities, alternate entrances, and alternatives to queuing are common.

Unfortunately, alternate options can be perceived as exclusive, premium amenities, leading to resentment or exploitation by those not meant to use them, and contention and suspicion among guests over entitlement to the accommodation. The contention occurs when alternate options are not only accessible, but have features everyone would like, such as more comfort and less queuing, especially if it also involves less wait time. Like proximity parking, queue bypass inspires many people to look for ways to access it.

Attractions may decide that the solution to a much-desired exclusive accommodation is to turn it into the inclusive mainstream operating model. Offering virtual queues to everyone can reintegrate can’t-queue guests, don’t-want-to-queue guests, and everyone in between.

However, there are reasons an alternate access option may make sense. Increasingly, queues and preshows provide extended opportunities to foreshadow the attraction with rich scenery and media. Alternate access by skipping the queue could deprive a wheelchair user of this element of storytelling. However, the primary queue may not be as inclusive as it seems. From a wheelchair point of view, it may consist of 75 minutes spent surrounded by crotches at eye level, and no clear sightlines to scenery. Even with an equivalent wait or return time, an alternate access path with an added preshow experience may be better than accessing a primary queue for wheelchair users. Alternate formats may even enable guests who are not physically able to join an experience to access an alternate experience through virtual, augmented, or mixed reality media.

Where to find guidance

For insight into the actual, rather than idealized, experience, engage with people who have the disability, including professional designers and your guests. Non-disabled designers visualizing the experience of disability often focus on the difference or the loss, compared with their usual experience. Through experience, we develop day-to-day coping strategies and insights into what works that are not self-evident to someone experiencing an “empathy” exercise. We notice things that a focus group consultation would not ask. For example, designers may consult deaf consumers for input about different types of media devices for accessing a show. The consultation always assumes that we will ask an employee for the device on arrival at the attraction. This fails to understand that talking to people is the very thing that this disability obstructs.

Designers and operators often receive ample family feedback and requests. Calming respite facilities are becoming popular as a result of parent requests in response to autistic children who cope with sensory stimulation by appearing overwhelmed. Some of my grad students a few years ago identified with sensory processing disorder and thus were curious about this. They embarked on a field trip expecting to return with specifications for respite facilities. To their surprise, the park, the attractions, and even the crowds in the queues were not overwhelming, while they were following their own plans. Their experience of sensory overload occurred between plans, because of the richness of possibility. This does not mean that they did not fidget in line, but that fidgeting was not perceived as problematic behaviour, because it didn’t bother them, and they were where they chose to be. Parents are voracious advocates for their disabled kids. However, for every child with a disability, there are adults who used to be children with that disability. You will hear from parents – but consider also asking disabled adults to share their own childhood recollections.

Another common source of guidance is accessibility service providers. Especially in the case of deaf guests, it is understandably more convenient to talk with a hearing person who knows sign language than it is to converse with me. However, attractions have quarantined me in front row seats that give me an unparalleled view up the sign language interpreter’s nostrils, uncomfortable head-neck posture, and no sightlines to any other elements of the experience, because that is where the sign language interpreter told them I should sit. If your team does not include disabled designers, communicating with disabled guests is essential in design, in development of alternate experiences, and in the everyday operational setting. Ideally, have those conversations directly.

You want to ensure that you can tell your stories to everyone, including guests with disabilities. They have stories to tell you as well.