By Dr. Kathryn Woodcock

Design conventions affect how people access entire categories of experiences.

ABOVE: President George H.W. Bush signs the Americans with Disabilities Act into law, July 26, 1990. Credit: George Bush Presidential Library, National Archives ID: 6037489

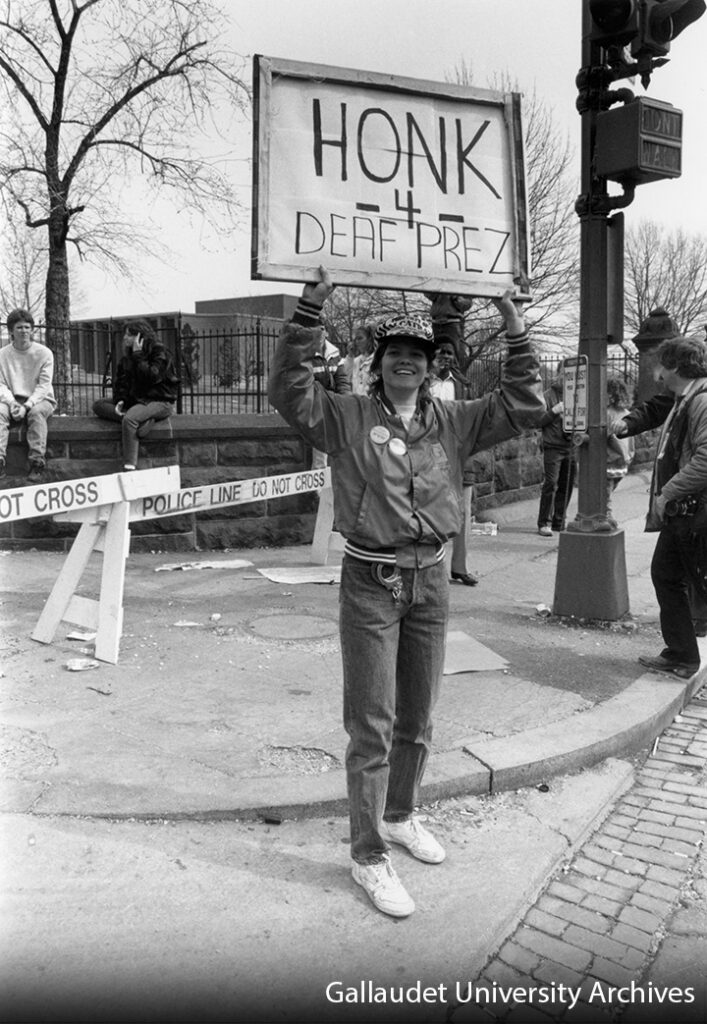

I am proud of the role my Deaf peers played in the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, more than 30 years ago. The Gallaudet University protests, successfully demanding the appointment of a Deaf university president, on the doorstep of the seat of the U.S. government, raised the visibility of disability issues and supportive public sentiment, and tipped the deliberations in favour of the ADA[1] (and saw Dr. I. King Jordan become the first Deaf person to lead this Deaf institution in its 124 years.) The ADA includes general and specific obligations for public and private sector entities to redress access barriers to people with a wide range of disabilities. Responsible businesses, including theme parks and attractions, have established programs to ensure compliance with ADA.

Learning of my vested interest in accessibility and inclusion along with my expertise in human factors in my field of engineering, professional colleagues often ask me for guidance on ADA requirements in relation to specific types of themed experiences. As a non-American, the letter of U.S. law is literally foreign to me, but I keep a principled distance from ADA compliance because ADA compliance is not accessibility, and it is definitely not inclusive design. Parts of the ADA are obsolete (such as its enthusiasm for TTY devices, technology ostensibly offered for MY benefit, but which I have not used since 1999) and all of it is the lowest common denominator.

Missed opportunities

My position has long been, “Disability is not an objective condition that you have or don’t have.” Every person will encounter things they cannot do for one reason or another. Certain design conventions make that a more frequent experience for some people than it is for others”. Those design conventions often affect how people access whole categories of experiences. As King Jordan famously said, “deaf people can do anything hearing people can do, except hear.” But if opportunities are wrapped in a structure that requires that people hear, their other skills will be squandered if they cannot hear.

Dr. Woodcock notes: “The blank space under the TTY pictogram may seem to be an ADA concern, but it’s 2021! Deaf people use text messages nowadays.”

In the U.S., the ADA responded to a groundswell of frustration over wasted capacity, essentially saying, “If you will not voluntarily evolve those design conventions, we will codify them for you.” As such, certain commonly excluded groups of people have explicit rights under ADA. That is why “disability” is taken as a positive identity, and not an embarrassing condition in need of a euphemism: The identity unlocks essential rights…in the U.S. Other jurisdictions may have formally protected no groups explicitly, or different groups. Attractions may exclude other types of people through other design conventions. All of those are equally problematic. If you ask me about access, I will talk with you about access, not ADA compliance.

ADA jargon

Returning from that detour, then, the meaning behind my headline is that, over the years, I have noted “ADA” emerging into business jargon as a description of the guests themselves, or of facilities designated for them. While the actual Americans with Disabilities Act applies to a wide spectrum of disabilities, “ADA vehicles” are usually the wheelchair-accessible ones. Designers scrutinize ride systems to determine how they will be used by “ADA guests” and team members are instructed how to be ready for “ADA guests.” Planning for “ADA guests” usually brings to mind wheelchair accessible parking spaces, step-free entryways, spacious washroom stalls with grab rails, and provisions for transfer from wheelchair to ride vehicle. None of those commendable and necessary provisions obstruct people with other disabilities, but neither do they accommodate other disabilities who are equally entitled to access under ADA including, say, Deaf people.

But even that isn’t the reason I’m not an “ADA guest.” I would say the same if I was a wheelchair user. The terminology “ADA guest” and “ADA vehicle,” “ADA entrance,” “ADA experience,” etc. presumes that it is an alternative – or worse, a category restricted from an experience.

I am not an “ADA guest.” I am a guest. I have some abilities – and lack some others – just like every other guest.

Whether you think you need to restrict me or direct me to an alternate experience depends not on me, but on how you designed your experience.

Access and choice

With enough variety offered, everyone has 100% of an experience.

When I think about accessibility, I don’t think of it as a binary identity or characteristic (“ADA guests” vs. non-ADA or “normal” guests). I think about the infinite variety of individual differences. Visualizing all guests as different is more realistic and accurate than visualizing all guests the same except the disabled ones. Access laws such as ADA have simply given legal rights to people with disabilities.

None of the following context can guarantee that no disabled guest will be excluded, nor assure you that excluded guests will be satisfied with exclusion, but a respectful process can avoid needless dissatisfaction.

Reckoning with inclusion at the gate level is the simplest starting point. A venue that offers an experience that works on many levels will more innately facilitate access. Nobody experiences everything. Nobody experiences anything the same way. With enough variety offered, everyone has 100% of an experience. From theme parks to carnival midways, many attractions already quite capably balance their offerings to provide “something for everyone.” Guests customize their experience to optimize enjoyment and value within the spectrum of offerings. A group of guests will choose their destination based on suitability of experiences and adequate value for everyone in the group. This is especially important with costly all-inclusive ticketing. As long as everyone can enjoy 100% of a day’s value from their admission, each person may experience the day differently, yet still feel included and satisfied.

Just as there are “normal” guests who dislike and will avoid getting wet on a ride, or riding a simulator attraction, or being at a high elevation, there are disabled guests who may simply abstain from certain kinds of experiences that don’t work for them. They may opt out of attractions that present 3D media incompatible with their monocular vision or visual processing or style of prescription eyewear. They may skip rides and shows with expository narration that lacks transcription or has transcription that conflicts with enjoying the scenery. They may abstain from attractions that aggravate anxieties about going upside down or into scary, dark, enclosed spaces. They may not even consciously associate those as accessibility barriers – rather, simply perceiving it as a voluntary choice in the context of many other options available at the venue.

Choice vs. exclusion

Voluntary choice is a critical element: Being informed about the nature of an experience, recognizing the unsuitability, and making a choice to abstain. This is different from unilateral exclusion by an operator-imposed restriction, which takes away not only access but also autonomy, contributing to dissatisfaction.

While voluntary choice eliminates the dissatisfaction of imposed restrictions, some guests may be unhappy with a limited selection of accessible attractions. People with disabilities and other conditions and sensitivities want to be able to share experiences with their companions, just as others do. This is particularly the case when an attraction is a blockbuster because it is linked to culturally resonant IP, or the attraction itself has become a cultural touchstone.

Dr. Kathryn Woodcock. Credit: Technical Standards and Safety Authority

A venue can’t tell guests which experiences to want. Only the guest can decide what they want. Guests are entitled to be disappointed when experiences they want are inaccessible or intolerable to them. It should be no surprise that people would think that an experience covered in national media or prominent Top-10 lists should be inclusive.

Accessibility is not simply a matter of having a large number of options, with a subset of options designated as “accessible.” Accessibility is having an experience as satisfactory as anyone else’s experience. Attractions with effective inclusion build market interest and loyalty; they also get a lot of love in consumer forums focused on disability.

Communication

Operational staff need to be prepared to respond when guests ask about access or request alternative options. It will often be most effective for the front line to automatically escalate these inquiries to a properly prepared supervisor who understands how to talk about disability and what is possible. Responses may cover the spectrum, from explaining the attraction experience in relation to the guest’s abilities, to arranging what the guest has requested, to counter-offering a planned, alternate accommodation.

It’s important that the supervisor be able to speak directly and without embarrassment. Some front-line staff will be uncomfortable discussing the guest’s need. The basic hiring pool – society at large – still misunderstands disability as something shameful, often falling into euphemisms. When we describe ourselves a certain way, we don’t want corrections. When I say “I am Deaf,” I don’t want someone responding to me with “what we do for hearing-impaired guests.” At a moment when a situation is on the precipice of escalation or de-escalation, respecting the guest as the expert on their identity is simple – and essential.

The greater the dissatisfaction, disappointment, or perception of disrespect, the greater the chance the guest will take recourse in an assertion of legal rights. The outcome of a legal challenge cannot be predicted: Cases with similar facts have been decided differently. Whether the guest or the operator will prevail depends on the specifics of the attraction, the guest, and the jurisdiction. What is certain is that in the process, the dissatisfaction and unmet access expectations take the spotlight away from other inclusive initiatives, efforts, and intentions.

This article is the first of a three-part series by Dr. Kathryn Woodcock.