Designing to celebrate and protect animals

by Jeremy Railton

I grew up in the mid-1950s, on my family’s farm in Central Africa, 40 miles from the Victoria Falls. As early as I can remember, I would entertain myself for hours on end by drawing everything around me – lions, wart hogs, baboons, Kudu, duiker, stem buck, Impala, rabbits and tortoises. My father, while he appreciated my early rendering skills, would have preferred if I had learned how to chop firewood.

On Saturdays, cattle from miles around were herded in and pushed through a plunge dip to rid them of ticks. It was quite a spectacle for a seven-year-old. I remember an occasion when a large Kudu bull got himself caught up in the melee of horned cattle. Just before he reached the plunge, he leapt (as only a Kudu can leap) and finding himself trapped in the farm yard, jumped over fences, zoomed past the trading store and ran through the vegetable garden, trampling my mother’s roses, until he was finally confronted by the trading store tailor holding a little spear, which he valiantly threw at the animal. It bounced off the tough hide and bent in two!

Later that day, I was having afternoon tea with my 80-year-old grandmother. Seeing me flushed and jabbering with excitement from the Kudu bull adventure, she said something that has stayed with me my whole life: “I have to apologize to you for my generation. We have ruined the Earth. We have killed the great herds of Africa, wiped out the buffalo and made the Quagga and the passenger pigeon extinct.” Her confession stunned me and changed my point of view in an instant. My familiar world consisted of our family farm and the tribal kids that I played with. Elephants, lions and leopards were a natural part of the environment. The idea that they could vanish had never dawned on my bush kid mentality. Her words planted a seed that grew into a lifelong interest in wildlife and environmental conservation. This was my basis for telling animal stories, which I’m still doing to this day.

My fascination with animals extended to an intense interest in birds. I registered with the Ornithological Society and started turning in egg records and bird check lists (which I still have). I foresaw two career choices in life: game warden or artist. Artist seemed likeliest, but I also knew the importance of earning a living. Life on the farm was paradise, but our economic survival was always tied to the vagaries of nature. A thousand-bird flock of Quelea birds, a herd of wild pigs or a few nights of porcupines in the corn field could ruin a crop, all the while that our eyes were turned to the sky for signs of rain.

My first job after high school was painting dioramas for the Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe, in Bulawayo. Under the direction of head artist Terry Donnelly and taxidermist Terence Coffin-Gray, I learned how to convey the visual narrative of a scene. They taught me that closely observed details – animal tracks, dung and accompanying insects, plants and geography – explain more about the life of the animals than just the animals themselves. This helped me later in my professional design career especially in theatre, theme parks and of course animal shows and experiences. Storytelling is key to all of them.

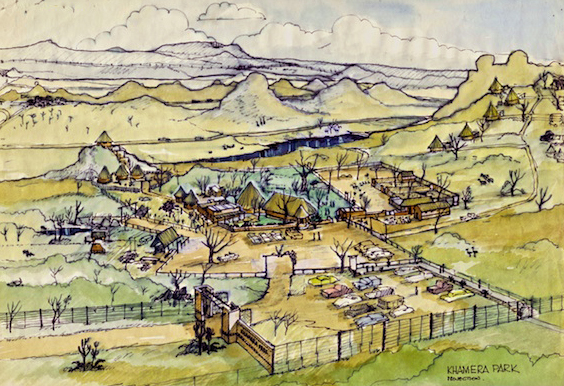

From Zimbabwe to Hollywood

In the early 1970s, my parents, Jack and Dorothy, sold our farm and bought 5,000 acres adjoining the Khami Ruins National Monument – former site of a 14th Century civilization in Zimbabwe and now a UNESCO world heritage site – to create Khamera Nature Park & Wildlife Sanctuary. It had good tourist access, exquisite scenery, Bushmen rock art paintings and a magnificent Baobab tree. I did my first master plan, designing a tea room, restaurant, craft village, site museum and overnight chalets. Because of our farming background, my family thought naturally along the lines of “organic” and “sustainable,” today’s buzzwords. The park was a success, and my parents ran it until their deaths in 1981. It offered garden teas, camping, walking tours, nature study and more.

By the early ‘90s, I had designed for theatre, dance, film, and TV, theme park attractions, live concerts and shows. I started to think about how I might integrate the earlier part of my life – my love of and connection to animals, especially birds – while living in the middle of Los Angeles.

From Hollywood to zoos

A friend introduced me to Steve Martin, one of the best-known animal trainers and bird behaviorists in the world. Steve has pioneered the art of training through positive reinforcement and his use of non-traditional, free flight birds combined with an inspiring conservation message sets his shows apart from many other animal shows. Steve invited me to work with him on designing a bird show theatre for the National Aviary in Pittsburgh. Shortly after, he hired me to come to Singapore and work with him and Angie Milwood of Precision Behavior to consult on concepts for new, outdoor shows at the Singapore Zoological Gardens, one of the first ‘open encounter’ zoos in the world.

My favorite show concept for the Singapore property was for “Village of Lost Pets,” to be enacted by animals with hidden trainers who would come onstage for the finale. Lost pets – dogs, cats, rabbits – come to a village where there are no humans. They go about their daily chores when a group of hooligans show up. The animals hide, but when the hooligans drop lighted cigarettes and litter, the pets sneak in and clean it up. The message was an emotional one of conservation, empathy for animals and the heavy footprint of humanity.

Although “Village” was never produced in its entirety due to budget issues, working with Steve and Angie helped me realize that my “Hollywood” design experience could fold into my love of animals and my desire to make a difference. I didn’t have to just stand by wringing my hands.

SOAR at the San Diego Zoo

I also collaborated with Steve and Natural Encounters on “SOAR – A Symphony in Flight” – a nighttime show that ran at the San Diego Zoo, opening in June 2009. The idea was for visitors to have a beautiful, emotional experience of watching birds free flying to music and to tell a story without the usual constant banter of the trainers on headsets that can often upstage the birds. (Give the audience time to sit back and enjoy the beauty without the distraction of one-liners!)

SOAR began with a darkened stage. The sound of flapping wings broke the silence, and in silhouette, a giant bird flew above the heads of the audience in a memorable opening encounter. One of my favorite moments came a beat later when a cell phone started ringing in the pocket of an audience member (in fact, an actor plant). As the guy started to have a loud conversation, a crow flew out, took his phone and dropped it into the pond on stage. The show started with the audience laughing, cheering and clapping!

As a production designer, my role is to serve the intentions of the director and writer, just as when I work on a movie or big stage show, and for the finale of SOAR, I was able to redesign a magical illusion that I had used for a Diana Ross tour. The effect was to make a Marabou Stork come to life from an image projected onscreen. It depended on the stork walking through an invisible panel composed of vertical strips of elastic, overlapped and projected on so that they appeared to be a solid piece of scenery. Steve’s genius was to teach the stork to walk through the strips on a precise cue that made it seem that the onscreen image had suddenly come to life. The stork then flew off to cheers from the audience.

Crane Dance for RWS

In 2007, Lim Kok Tay, Chairman of Resorts World Sentosa, asked me to create a dynamic work of public art to embody the spirit of his new resort – something big and impressive. The first idea was to do a show using giant construction cranes, with their movement synchronized to music and lighting. How would I create an emotional connection between the audience and a piece of construction equipment?

One night, staring at my drafting lamp, it occurred to me that it had the basic joint articulation of the Crane, a well-known symbol of health and longevity in Asian culture. Musing on the double meaning of the word ”crane,” and as a bird lover familiar with the birds’ mating dance, I started to pose the lamp in various positions. I attached a second lamp, began to envision two giant cranes dancing, and sketched out a 10-minute love story. “Crane Dance” opened in 2010. It continues to be widely celebrated, and received a Thea Award for Outstanding Achievement from the Themed Entertainment Association. The original concept included several digital displays of information about the International Crane Foundation and their efforts to protect the beloved species – a feature that unfortunately did not make it into the final version of the show.

The bird population of China has suffered many setbacks and loss of habitat. Working with a Beijing landscape designer, I designed an attraction that would provide a safe haven for wild birds by planting indigenous trees, grasses and shrubs to attract them.

I have designed many attractions in China and Asia; unfortunately this one remains unbuilt. The Happy Birds Garden, as we called it, offered a multi-level nature experience that would educate and entertain guests of all ages and levels of health and physical ability. A gentle wooden walking path on stilts rose and curved through a variety of nature experiences as it wound over streams and ponds. The walking path connected to a series of special function decks that provided digital displays of endangered birds in the region as well as audio recordings of their unique songs.

And that brings me back to my grandmother in Zimbabwe in the 1950s. Recently, some friends visited me from Africa. Fifty years ago, they had conducted a survey that counted 2,500 Rhino in the Mana Pools, a wildlife conservation area in northern Zimbabwe. Today there are only 120. Reflecting on the shocking destruction of animal habitat and the loss of species in my lifetime reminded me of my Grandmother’s apology to me, that had propelled me into a different way of thinking.

And here I find myself back in the same position as she, wanting to apologize for my generation, to take action, and inspire others to act. We must all go beyond simply apologizing. I want to continue to do my part as an artist, designer and animal lover. I continue to embrace and seek opportunities to inspire the care and conservation of animals and their habitat. I hope to be in a position to continue to design authentic animal experiences that build an emotional arc, bringing humanity closer to understanding its responsibility for stewardship of the animal realm. • • •

Jeremy Railton is Chairman/Principal designer of Entertainment Design Corporation, http://entdesign.com/.

Jeremy Railton is Chairman/Principal designer of Entertainment Design Corporation, http://entdesign.com/.