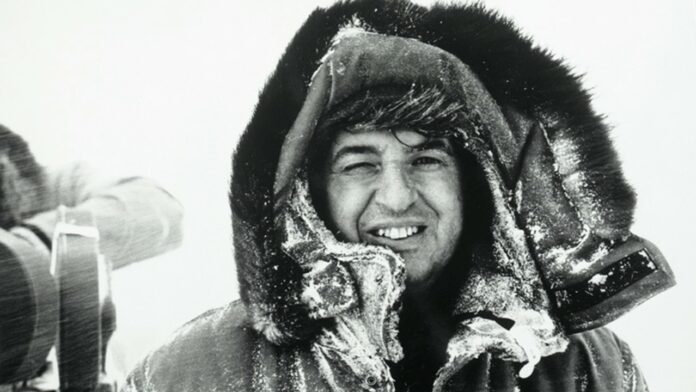

ABOVE: Graeme Ferguson in Antarctica, 1965, filming the multi-screen production “Polar Life” for Expo 67 Montreal. From Ferguson’s personal collection.

Giant screen cinema pioneer Graeme Ferguson passed away on May 8, 2021 at age 91, just eight weeks after the death of his wife, Phyllis. Ferguson was one of the original four co-founders of Imax Corp. (with Bill Shaw, Roman Kroitor and Robert Kerr). They developed the groundbreaking 1570 film format that launched an industry and redefined documentary filmmaking. The IMAX format, introduced at Osaka Expo 70, was embraced as a medium for world expo pavilions, and adopted by science centers, leading to the creation of a permanent theater network that became a new arm of business operations for these educational institutions, and eventually led to commercial installations as well. Ferguson’s own films were influential, groundbreaking works, such as Tiger Child and North of Superior. His work was germane in the creation of the space and underwater documentary genres, changing people’s perspectives on the world and the universe. From astronauts to filmmakers to projectionists, Graeme Ferguson touched lives and careers and fueled creativity.

InPark’s Judith Rubin and Joseph Kleiman, who have been active in the giant screen sector for decades, reached out to their networks to build this story. We thank the contributors for their heartfelt testimonials and for sharing photos, to help us capture a bit of history and honor Ferguson’s incalculable achievements.

DENNIS EARL MOORE, Filmmaker/Producer

I met Graeme Ferguson in 1967 at Expo 67 Montreal. I went with a colleague from Cleveland, OH, where we were starting a photography school. There was a subway strike in Montreal at the time, and to get to the fairgrounds we had to walk over perhaps 15 sets of train tracks, and then still cover some distance to the park. Ten years later, I was again in Montreal, doing a three-screen presentation for the mayor about the expo!

Anyway – after being immersed in the multiscreen show Polar Life at the expo, with 11 screens and rotating seats, I was quite eager to meet Graeme. Luckily, we met that evening for drinks. Needless to say, the conversation was quite inspiring.

In the mid-1970s, I met Graeme again when I started working with Francis Thompson on an IMAX film, American Years, for the 1976 Philadelphia Bicentennial celebration. Of course, Francis had known Graeme since the 1950s. By the way, in 1974, there were only two IMAX cameras; you had to get on the schedule for one!

Graeme made some interesting and very important films in his life, and basically what he did changed my life – the experimental concepts, a whole new environment… It was just fantastic, simply sitting there in an IMAX theater, surrounded by imagery – it was a complete, visual experience that at the time was unprecedented. You could look around and decide what you wanted to focus on. I went on to make my own giant screen films of course, Living Planet and Flyers.

Now I’ve got tickets to go see the immersive Van Gogh presentation here in New York City, and it hearkens back to what Graeme did with Polar Life back in 1967. He predicted something with that. It changed my life and a lot of other people’s. It brought back the documentary style of filmmaking to bigger audiences – it was about place, the idea of going someplace and being immersed in an environment – and it got me around the world. Interestingly, both Graeme & Van Gogh had a strong sense of how to convey time and place.

SEAN MACLEOD PHILLIPS, Director/Cinematographer

All of us working in this industry owe our careers to Graeme Ferguson, who along with Roman Kroitor, Robert Kerr and Bill Shaw literally invented the giant screen experience.

Graeme was the most universally respected producer working in the format, and he was very easy to talk to and always had great advice from the creative to the technical with a lifelong passion for the giant screen. He will be missed.

STEPHEN LOW, Filmmaker

My favorite Graeme Ferguson story goes back to the dawn of IMAX. As a teenager in an NFB family [Stephen’s father was famed National Film Board of Canada filmmaker and IMAX collaborator Colin Low], I was getting most information second-hand at the dinner table, but here goes.

As I recall the story, two 30-something filmmakers were preparing to host a Japanese delegation in Montreal. The Japanese were looking for new exhibition ideas for their 1970 World’s Fair project [Osaka] and the young Canadians had a big idea to sell. They rented an office space for a day or two, filling it with rented furniture and busy-looking family members and friends. But when the delegation arrived, they began the tour with a trip to the NFB studios where one of the filmmakers actually had a small office. Going in the front entrance they made a detour up the main stairs past dozens, or perhaps hundreds of awards, including a row of Academy awards. The NFB was in those days a very impressive place with giant sound stages, mixing boards, cafeteria, and they showed it off in some detail.

After lunch they went to their “actual” office downtown with the busy actors making important calls and rushing around. Somehow the Japanese were mightily impressed with the whole experience. It must have seemed to them a large and very successful endeavour, and the question of who owned what was successfully fuzzy. The young filmmakers, Graeme Ferguson and Roman Kroitor, closed the deal to create the first IMAX film for the fair, and with Graeme’s high school friends engineer Bill Shaw and businessman Bob Kerr, proceeded to create an entire new industry inspired by and sustained by ingenuity, creativity and the highest possible standards.

It’s quite possible my memory of this story is not completely reliable, but anyway, it sums up what I loved about Graeme and the other founders, and working in the medium they invented and the industry they created. You have a great idea that you believe in, even if no one else does, and you just throw yourself at it with everything you have. I was fortunate enough to progress from IMAX-adjacent teenager to actual IMAX filmmaker, and although as a Montrealer I had a closer relationship with Roman, I still count myself lucky to have had a half-century relationship with Graeme, beginning with working for him as an aspiring young filmmaker and ending as two oldies, with dozens of films between us, grateful to be sharing stories and memories, encouragement and advice. He will be dearly missed.

GREG MACGILLIVRAY, Filmmaker

When Jim Freeman and I first met with Graeme Ferguson back in 1974 as we were beginning the production of our first IMAX film To Fly, he could not have been more helpful. He guided us with ideas for how to structure the film and helped us whenever we ran into problems. I’ll never forget the day when Jim and I flew to Toronto to meet with the IMAX founders. We were there to discuss improvements to a new IMAX camera we needed to shoot To Fly. We all went to Ontario Place to watch the only other three IMAX films in existence, then to IMAX’s offices where we sat on camera boxes in the garage. Jim made a proposal to Graeme and Bob: “If we come up with enough money to build three new IMAX cameras, can you build them in six months so that our team can make two new IMAX films for the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence?” Their faces lit up. “Let’s start now!” they said. The cameras were done early. Jim and I went off and make To Fly, and our partner, Francis Thompson, who had raised the money for the films, made the epic 50-minute IMAX film American Years for the Philadelphia 76 temporary IMAX theatre.

Over subsequent years, Graeme helped our company establish itself in the IMAX production world, and for a long time, our companies were joined at the hip as we tried to build an industry that provided the best entertainment experience in the world. I can think of more than 20 examples where MFF teamed up with IMAX Corporation on various theater builds, film productions, and equipment development. Graeme was my mentor, as he was to so many others in our filmmaking community, and it is clear that the IMAX world of today would never have been possible without his creative vision and inspiration.

One thing that always impressed me was that Graeme always wanted to share the limelight with others. He was the co-founder of IMAX along with his boyhood friends, Bob Kerr, Bill Shaw, and Roman Kroiter, who are all recognized as pioneers of the best motion picture experience ever conceived. Happily, I was able to exchange many emails with Graeme these past few years as he contributed stories and ideas to the book I’m writing about my filmmaking adventures over the past 60 years. Graeme figured in many of those adventures, and I was able to express to him how grateful I was for his help and how grateful our industry is for his guidance and creativity. He and his wife Phyllis will be missed dearly, by me and by everyone at our company. He was one of my heroes, and it saddens me deeply that he is not here to help guide us further.

DR. KATHY SULLIVAN, NASA astronaut

My favorite memory of Graeme has to do with the scene in The Dream Is Alive, where Dave Leestma and I, spacewalking out in the cargo bay, float up into the aft windows and wave to our crew mates inside the shuttle cabin. We got that idea when Graeme brought us to the National Air & Space Museum in Washington, DC, to see the rough cut of the still-in-progress film. The aim of the trip was to sharpen our sense of how the scenes from our flight would fit into the storyboard and complete the film. The STS-41D footage included a cool shot looking out the aft and overhead flight deck windows to the Earth sliding by below. We thought the angle was really cool and then realized, “we could shoot that with people looking in the windows!” We kept the idea entirely to ourselves; never said a word to the IMAX team. I think we knew within seconds when that scene came out of the processor, though, because our phones lit up with ecstatic calls from Graeme and Toni [Myers]. I still chuckle every time I see it, partly recalling their great delight and partly laughing at myself, the geologist who gave her crew mates a quick wave and then turned to look back at the Earth below.

ANDREW GELLIS, Magnetic3D.com

When I first met Graeme it was in Vancouver. He was most kind and a very gracious man. I was escorting a group of SONY executives to experience IMAX and discuss the Lincoln Square project, what was to be a purely commercial venture. It was important to Graeme as he already knew that IMAX’s financial survival was predicated on opening new markets and broadening the audience and the 1570 format’s reach. Even after IMAX became a public company, he was a hugely supportive presence and when I joined the Company, he was a wise counsel, a champion of what he and his original partners had created, and a friend to all of us at work in the glorious world of IMAX. God bless him and Phyllis. It was an honor to have known and worked with them.

MARY JANE DODGE, MacGillivray Freeman Films

I’ll never forget the first time I met Graeme Ferguson. It changed my life. I was walking through a trade show at a planetarium conference in 1977 and met a nice man passing out brochures on something called “IMAX.” I said, “IMAX, what’s that?” It was Graeme Ferguson and he told me all about IMAX. That started a conversation that lasted a lifetime.

I was one of the lucky ones that started working in this industry at the very beginning and got to see it grow and thrive. Graeme was just the leader we needed in those early days. The museum world is different from commercial filmmaking, but Graeme just fit in perfectly! He could speak their language. At the same time, filmmakers were experimenting with every film, and Graeme was a visionary collaborator with them all. We all needed each other to build this new industry and Graeme led the way. He was always thinking about the future too and what was coming next. That’s what helped build this industry and in so doing left a legacy that stretches to the stars and back. We all got to take that great ride with him. And we all know we couldn’t have done it without him.

As a film director, he used this dazzling new IMAX format to take us places that only a few can see first-hand – like looking at our beautiful planet from space. And was equally as profound with images on Earth. Who can ever forget that opening scene in North of Superior? The camera hovering fast and low over that great lake, with that mesmerizing drumbeat. It was so new, so compelling such a great use of the medium and the message. It was quintessential Graeme Ferguson. Heroic. Inventive. Unforgettable. Legendary. Just like the man himself.

DIANE CARLSON, Giant Screen Cinema Consulting LLC

Graeme Ferguson’s artistic vision for an immersive film experience created an industry that has educated, thrilled and entertained millions of people worldwide. I had the privilege of knowing him for nearly 40 years. I first met him at Pacific Science Center in Seattle where my program responsibilities included the Eames IMAX® theater and eventually also the Boeing IMAX® Theater with laser. I became involved when there were only 14 IMAX projectors installed worldwide. And the co-founders took the time to visit our theater for film openings.

Graeme was always such a gentleman and a wonderful goodwill ambassador for Canada. We shared much time together in many settings from conferences to international expos and even on his beautiful, turn-of-the-century wooden boat on Lake of Bays in Ontario. And conversations with him were always fascinating and informative. He was a wonderful storyteller and teacher. His stories were told not with bravado but with gentle humor and grace. I am sure that his style is what helped get the IMAX cameras into space and to set the stage for the ongoing relationship with the National Air and Space Museum and NASA.

Another tribute to his talent was the wonderful team of people that he surrounded himself with and who were with him for not just years but for decades. He helped shape my career because the IMAX® theater at Pacific Science Center was one of the reasons that I was willing to leave the Lawrence Hall of Science at the University of California, Berkeley for the post in Seattle. And I became passionate about the IMAX experience—his creation. He will be missed, but his giant vision continues.

CARSON MALONE, Pulseworks

In May of 1996, I was nervously awaiting the arrival of Mr. Graeme Ferguson at the Chattanooga airport in Tennessee. The Co-Founder of IMAX was on his way to my town to help cut the ribbon at the Tennessee Aquarium’s brand new 400-seat IMAX 3D theater, an adjacent stand alone addition to its main facility and one of only a handful of large format theaters with 3D capability in the US at that time. As theater start-up manager, I had been part of the planning and marketing efforts and was excited to see this long-awaited day finally come. My present assignment, though, was to pick up this VIP named Graeme Ferguson and drive him to the launch day ceremonies. The Tennessee Aquarium had opened four years earlier to much acclaim and had seen an overwhelming annual visitation that was more than double what anyone had predicted or anticipated. The launch of the world’s largest freshwater aquarium had spurred a renaissance in that city, transforming a once a tired industrial town of aging factories and warehouses into a scenic riverfront community full of culture, nightlife and family fun. Annual visitation to the attraction was at least five times that of the community’s population of 300,000, and now four years later, on the anniversary of our grand opening, we would bring the special IMAX film experience of “being there” to millions of new visitors. It was a proud day for our humble City.

Admittedly, I was concerned about what Graeme would think of us. This was not New York, Vancouver or Poitiers, France…heck, it wasn’t even the sunny seaside of Galveston. This was Chattanooga, the home of the Chattanooga Choo Choo and scores of crumbling red barns with roofs that had “SEE ROCK CITY” painted on them. As I entered the airport lobby, I braced for any sign of letdown or humiliation on my Guest’s face. To my surprise, the first words from his mouth were, “What a beautiful place!” He was so gracious and genuinely impressed by our community.

I hurriedly drove him to our newly-built theater for a sneak peak (he did the customary “clap test” on the theater’s acoustics) and a tour of the projection room, which he glowed in approval of. Then it was time for Graeme and I to enter the back seat of an open-air convertible sports car and take part in something of a legendary nature…an old-fashioned grand opening parade! Our marketing team had arranged the most amazing press coverage of the launch ceremonies and assembled a downtown parade made up of high school marching bands and mascots, baton-twirling attendants, and volunteers waving banners and other fish-related props. The stately Graeme Ferguson and I were wedged firmly in between all this festive mirth in our chauffeured convertible with magnetic signs on the sides that had our names in big block letters! The streets were lined with throngs of cheering school teachers, students, surprised business people and other well-wishers and a cacophony of brass instruments and bass drums blared out “Octopus’s Garden” and other sea shanties into the air. Promising “More to “Sea” with IMAX 3D!”, our convoy triumphantly careened through the streets with Graeme and I waving like boy band celebrities on a Thanksgiving Day float. The excitement and scale of the event was surreal and we laughed afterwards about being sitting ducks in the back of that car! The launch was a tremendous success and our IMAX theater was soon one of the top performers in the country.

Graeme was always ecstatic about the parade. Over the next many years, whenever I would see him at conferences he would light up about that day in Chattanooga when our community showed him such generous appreciation and admiration for the immersive technology experience he helped birth. What’s more, if ever I spoke to his other IMAX colleagues about me hailing from Chattanooga, I would usually hear, “Oh, that’s the place where Graeme Ferguson was in a parade!” I was so honored to be a part of that moment.

CHERIE RIVERS, Chief Projectionist, Telluride Film Festival

I can’t imagine how my life would be if the IMAX projector had not been invented by Graeme Ferguson and his cohorts. I might never have moved to Boston and met my husband of nearly 33 years, and all the good friends I bonded with along the way. It has defined my career and shaped my life.

In the 1980s, as a projectionist working at the Eames IMAX Theater at the Pacific Science Center in the 1980s and the Seattle Omnidome, I had the opportunity to visit Expo 86 in Vancouver and get a behind-the-scenes tour of the IMAX theaters there. That is where I met my best friend Ingrid Lae (a longtime IMAX projectionist and theater manager). I found out about a new chief projectionist job at the Museum of Science Mugar Omni Theater in Boston, and immediately applied. Luckily, the GSCA (it was the Space Theater Consortium then) convened in Seattle that year and I was able to have a quick interview with Mary Jane Dodge, who hired me and opened the Mugar Omni Theater. After she left in 1989, I started programming the Omni Theater as well.

At the end of 1986, I started the job in Boston; the theater opened in March 1987. During that time, I met my future husband. We married in 1988. Our two children (now adults) basically grew up visiting the IMAX theater and Museum of Science.

I continue to be involved in the giant screen industry even though I am not currently working for a theater. I guess my ties have become so tightly woven with my life that it has become impossible to disentangle them.

It is hard not to be changed by watching a classic IMAX film. Graeme changed the way I and millions of others see the world today – inspiring people to visit other parts of the world and further their knowledge of the world around them, whether that leads them to go into a specific career or make changes in their lives that make a difference.

INGRID LAE, projectionist

I was extremely saddened to hear of Graeme’s passing. It feels like the end of an era, now that all of the founders of IMAX are gone. Their invention was pivotal in my career and I would not have had the job I loved for 35 years, nor met many of my friends, or had the experiences I had, in many parts of the world, were it not for IMAX.

I was just starting out as an apprentice projectionist when I first saw an IMAX film and made up my mind then that I MUST be involved with this incredible format somehow, although at the time, there were no IMAX theatres where I lived. Not long after that, two theatres were built in Vancouver for EXPO ’86 and I ended up working at both.

When I met Graeme for the first time, I was working as a part-time projectionist and I was in awe, but I found out that he was very down-to-earth and interested in any sort of feedback on how to make films, or the system, provide better experiences for viewers. He hung around in the projection booth with me while I shut everything down at the end of the day and then I drove him back to his hotel, chatting all the time. At the time, he was perturbed by certain scenes that induced motion sickness and was picking my brain as to how I thought that could be remedied.

I’m still amazed by what the founders achieved with the technology and Graeme in particular, with the creativity he showed in the films he produced.

IAN MCLENNAN, planetarium and museum consultant

I had the privilege of knowing Graeme Ferguson both as a young, ambitious and visionary filmmaker – and many years later as an elder statesman in the giant screen film industry. Graeme was a proud Canadian (recipient of the Order of Canada) but also had a global perspective and urgent sense of mission. His pioneering work with the US space program resulted directly in millions of people appreciating the beauty and wonder of the cosmos.

I first met Graeme soon after I was appointed managing director of Ontario Place, Toronto. That was the home of the world’s first permanent IMAX theatre, and Graeme’s wildly successful North of Superior had premiered at Ontario Place. Graeme was deeply concerned about preserving the unique qualities of IMAX in terms of any future productions, both for Ontario Place and beyond. At one point, we agreed it would be fun to create an IMAX experience whose only objective was to get people to laugh. Thus was born the idea of a film called Snow Job – a slapstick comedy about a hapless school bus driver (played by the hilarious comedienne, the late Barbara Hamilton) in the rugged Canadian winter.

Graeme was widely known throughout his life as a serious guy. No small talk with him! However, I recall with great fondness (and a bit of nostalgia) the two of us laughing uproariously at some of the dailies coming out of the Snow Job shoot. That is an image of Graeme Ferguson I won’t soon forget – partly because it was so at odds with his usual, even and dignified demeanour.

One of the memorable occasions involving Graeme Ferguson at Ontario Place was the visit by the famous American broadcaster/ adventurer, Lowell Thomas – widely credited with having “discovered” and promoted T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”) after the Arab Revolt (1916-18). Mr. Thomas had recently aligned himself with the dramatic new wide-screen invention called Cinerama – and he was interested in a tie-in with IMAX. I helped facilitate that meeting – which was held at Ontario Place. They remained in touch some time after that, although neither a technical nor corporate fusion ever took place.